|

"Maximilian D. Berlitz." In Immigrant

Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to

the Present, vol. 2, edited by William J. Hausman. German

Historical Institute. Maximilian Berlitz, born David Berlizheimer, was my first cousin

three times removed.

April 14, 2002 Marks the 150th Anniversary of the Birth of the Founder of the Berlitz School of Languages.

|

|

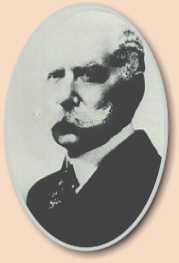

Maximilian

D. Berlitz,

founder of Berlitz School of Languages |

|

Newly Discovered Information Reveals His Origins.

Berlitz International Refuses to Accept New Historical Evidence.

Maximilian Berlitz gave his name to the first Berlitz School of Languages founded in 1878 in Providence, Rhode Island and the Berlitz method of language instruction. He used his personal history and mystique to develop his school into a company known around the world. He made headlines by teaching the Kaiser of Germany to speak English and by receiving medals of honor from the King of Spain, the government of France, and at many international expositions. He was and still is a symbol of that company. However, for more than 130 years the origins of the company founder have been shrouded in ambiguity and legend.

According to Berlitz International in its 120 Years of

Excellence: 1878-1998. (Princeton: Berlitz International,

1998), Maximilian D. Berlitz was born in 1847 and immigrated

from Germany to America in 1870. No mention is ever made of

Berlitz’s religion so one would assume that he was a Christian

emigrant. New information has been discovered that calls this

account into question. In the introduction of Berlitz’s

anniversary volume, the CEO and president requested information

regarding its founder’s life before his emigration.

When this credible historical evidence was fully disclosed to Berlitz International, however, its corporate officers rejected it in favor of much less reliable and less credible census data (September 20, 2001 letter from Michael Palm, Director of Marketing).

Also “when asked for a comment on the claims, a Berlitz

representative replied, ‘We are neither in a position to refute

or validate this story and thus, will continue to publish the

company history as it as been presented for the past 125

years.’” (December 06, 2002. ELTNEWS: The Web Site for English

Teachers in Japan).

This was despite the reality that a different date of birth—1852—was not hidden from the public or the Berlitz organization. 1852-1921 was inscribed on Berlitz’s headstone in the Woodlawn Cemetery in New York and was also printed on Berlitz’s official corporate photograph. One cannot help but wonder why.

Two historical researchers on both sides of the Atlantic worked together to uncover Berlitz’s true origins. Emily Rose, the American author of

Portraits of Our Past: Jews of the German Countryside (The Jewish Publication Society, 2001) and Dr. Adolf Schmid, president of the Baden History Association (Landesvereins Badische Heimat) recently discovered that Berlitz was born in the village of Mühringen at the edge of the Black Forest in southwest Germany. Maximilian Delphinius Berlitz was born David Berlizheimer in 1852. His father was a village cantor and Jewish religious teacher. The American dream was thus realized, not by the descendent of a long line teachers and mathematicians who was fluent in many languages, but by a poor Jewish emigrant.

A serendipitous chain of events made this discovery possible. In the course of the research of her Berlizheimer ancestors and the rural German Jews in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Rose in 1995 investigated the Berlitz-Berlizheimer connection. She had traced David Berlizheimer (born April 14, 1852) to America according to ship records in 1870, but then she had lost his trail. She queried Berlitz International about a possible connection; however they informed her that they had no information to support that theory. In a personal conversation, Berlitz’s grandson emphatically denied any family connection and stated that his grandfather was born in Prussia as Maximilian Berlitz.

Meanwhile in Germany, Schmid was writing an article on the Berlitz Company for the Commission for Historical Studies (Kommission für geschichtliche Landeskunde), only to be frustrated by the lack of information on its founder. In 1998 Schmid read the recently released Berlitz International’s commemorative 120th anniversary book that stated: “The date of his birth on his death certificate is April 14, 1852. However, U.S. census records suggest that the year 1847 is probably more accurate.”

In 1999 Schmid read the German edition (translated from English) of Rose’s book,

Als Moises Kaz seine Stadt vor Napoleon rettete. Meiner jüdischen Geschichte auf der Spur [When Moises Kaz Saved his Town from Napoleon: On the Trail of My Jewish History] (Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag, 1999). When he read, “without money or prospects,” in 1870 David Berlizheimer immigrated to America at age 18, he suspected that David Berlizheimer might be the same person as Maximilian Berlitz.

He wrote Rose in America who was of course taken by surprise because of the strong denial by Berlitz’s grandson and Berlitz International’s lack of information. Rose then obtained a copy of Berlitz’s death certificate that confirmed his date of birth, census data that listed Württemberg as his native land; and his naturalization papers that confirmed his immigration date as July 1870.

After Schmid published these findings in a German history review, several German national and regional journalists picked up the story. The Germans quoted in the newspaper articles were very proud of their newly discovered native son.

David Berlizheimer had made great efforts to create a new persona in America. Shortly after his arrival, he shortened his surname and changed his given name. He then married the Christian daughter of German immigrants and his children were brought up as Christians. Whether he cut off his ties from his Jewish

brother and cousins in Chicago and Philadelphia, or they from him, the families seemingly never communicated again.

Among the Jewish German immigrants in the mid-nineteenth century, his story was not unique, but it was certainly unusual according to anecdotal information. Accurate statistical records do not exist of those who intermarried and left the Jewish community, since often the goal of those Jews was to hide their Judaism and Jewish origins. In any case, it was perhaps more surprising that it was the son of a cantor and Jewish teacher who was the only family member who chose to live as a Christian in America.

As a recent immigrant Berlitz also created a new personal history. The company’s website and other articles state that Berlitz was descended from a long line of teachers and mathematicians, but this history—again most likely created by Berlitz himself—is only partially correct. He was indeed the son of a teacher, but actually he was the son of a village cantor- religious teacher. Although both his grandfather and uncles were lay leaders of the Jewish village community, his father was the first in the family not to work as a cloth trader but to train and then work as a not-highly remunerated village cantor-teacher. There were no mathematicians in the family.

The Berlitz International commemorative book states “he is said to have traveled extensively in his youth and to have been fluent in more than a dozen languages including all the major Romance languages and several Scandinavian and Slavic languages.” Rose undertook further research in the German archives that undermines these claims and also refutes the myth from company lore that Berlitz was so intelligent that with no prior knowledge he fixed a broken clock that even a clock shop owner could not repair. Rose found documents in which Berlitz’s widowed mother received a stipend to support her son in his three-year apprenticeship with a clockmaker. Berlitz’s unusual mechanical skill was thus explained at the same time his background in the training and teaching of numerous languages in Europe is further brought into question. Before his emigration Berlitz was living in one location learning a craft; he would not have had the opportunity to “travel extensively” to become fluent in so many European languages.

Rose includes the Berlizheimer-Berlitz connection and the detailed story of Berlitz’s background in her new book,

Portraits of Our Past: Jews of the German Countryside, published by The Jewish Publication Society in 2001. The story she tells is even more compelling than the personal history Berlitz created. Berlitz’s life epitomized the mythology of the poor young immigrant who lived the American Dream. It is inexplicable that the company Berlitz founded now refuses to embrace the true origins of Maximilian Berlitz, but perhaps it is honoring the wishes of its founder who chose to close the door on his past as David Berlizheimer — descendent of rural German Jews.

|